Links, annotations and related content by Woody Allen Mob Lynching

About Justice Wilk

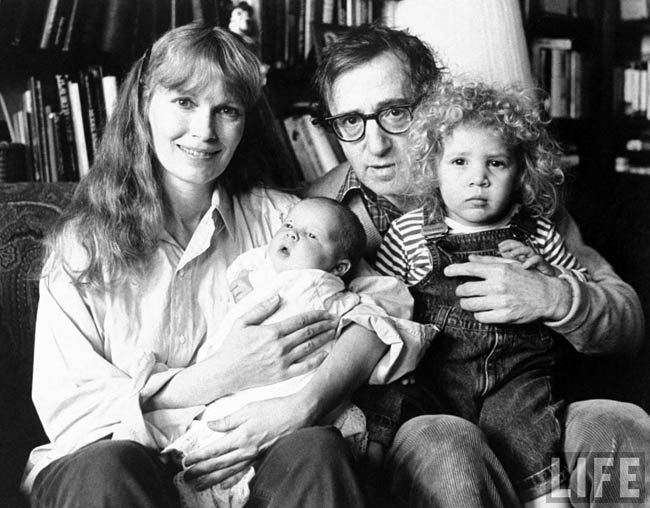

Because of Woody Allen celebrity and because he wasn’t showing remorse about his love relationship with Mia Farrow ‘s 19/21 years old daughter, Soon-Yi Previn, Judge Wilk’s conclusions are skewed by barely concealed revulsion toward him. To say he was openly biased in favor of Mia Farrow against Woody Allen is not an opinion but a fact.

If Elliot Wilk was still alive, maybe he could have been interested to learn some facts about Mia Farrow.

Justice Wilk was quite rough on me and never approved of my relationship with Soon-Yi, Mia’s adopted daughter, who was then in her early 20s. He thought of me as an older man exploiting a much younger woman, which outraged Mia as improper despite the fact she had dated a much older Frank Sinatra when she was 19. In fairness to Justice Wilk, the public felt the same dismay over Soon-Yi and myself, but despite what it looked like our feelings were authentic and we’ve been happily married for 16 years with two great kids, both adopted. (Incidentally, coming on the heels of the media circus and false accusations, Soon-Yi and I were extra carefully scrutinized by both the adoption agency and adoption courts, and everyone blessed our adoptions.) Woody Allen Speaks Out

In his autobiography Apropos of nothing, Woody Allen wrotes:

Finally, the gifted still photographer Lynn Goldsmith told me this story. She had been before Judge Wilk in a case where he ruled in her favor. A day later he showed up at her apartment unannounced and tried to sleep with her. When she resisted and pointed out he was married, it did not matter. He persisted. She finally got rid of him. Talk about exploiting one’s status. But that’s the kind of man I was at the mercy of.

Worst, as if it was not enough to make it a biased judge, Justice Elliot Wilk was married to an attorney who advocates for abused women and children and “believes the victim”.

Elliot Wilk dies at 60, in 2002, from brain cancer.

Allen v. Farrow (1993) – Justice Wilk

Supreme Court: The New York County

Individual Assignment Part 6

Woody Allen, Petitioner

– against –

Maria Villiers Farrow, also known as, Mia Farrow

Elliot Wilk, J.

SU24A

Index No. 68738/92

Introduction

On August 13, 1992, seven days after he learned that his seven-year-old daughter Dylan had accused him of sexual abuse, Woody Allen began this action against Mia Farrow to obtain custody of Dylan, their five-year-old son Satchel, and their fifteen-year-old son Moses.

As mandated by law, Dr. V. Kavirajan, the Connecticut pediatrician to whom Dylan repeated her accusation, reported the charge to the Connecticut State Police. In furtherance of their investigation to determine if a criminal prosecution should be pursued against Mr. Allen, the Connecticut State Police referred Dylan to the Child Sexual Abuse Clinic of Yale-New Haven Hospital. According to Yale-New Haven, the two major questions posed to them were: “Is Dylan telling the truth, and did we think that she was sexually abused?” On March 17, 1993, Yale-New Haven issued a report which concluded that Mr. Allen had not sexually abused Dylan.

This trial began on March 19, 1993. Among the witnesses called by petitioner were Mr. Allen; Ms. Farrow; Dr. Susan Coates, a clinical psychologist who treated Satchel; Dr. Nancy Schultz, a clinical psychologist who treated Dylan; and Dr. David Brodzinsky, a clinical psychologist who spoke with Dylan and Moses pursuant to his assignment in a related Surrogate’s Court proceeding. Dr. John Leventhal, a pediatrician who was part of the three-member Yale-New Haven team, testified by deposition. Ms. Farrow called Dr. Stephen Herman, a clinical psychiatrist, who commented on the Yale-New Haven report. What follows are my findings of fact. Where statements or observations are attributed to witnesses, they are adopted by me as findings of fact.

* I acknowledge the assistance of Analisa Torres in the preparation of this opinion.

Findings of Fact

Mr. Allen is a fifty-seven year old film maker. He has been divorced twice. Both marriages were childless.

Ms. Farrow is forty-eight years old. She is an actress who has performed in many of Mr. Allen’s movies. Her first marriage, at age twenty-one, ended in divorce two years later. Shortly thereafter, she married Andre Previn, with whom she had six children, three biological and three adopted.

Matthew and Sascha Previn, twenty-three years old were born on February 26, 1970. The birth Year of Soon-Yi Previn is believed to be 1970 or 1972. She was born in Korea and was adopted in 1977. Lark Previn, twenty years old, was born on February 15, 1973. Fletcher Previn, nineteen years old, was born on March 14, 1974. Daisy Previn, eighteen years old, was born on October 6, 1974.

After eight years of marriage, Ms. Farrow and Mr. Previn were divorced. Ms. Farrow retained custody of the children.

Mr. Allen and Ms. Farrow met in 1980, a few months after Ms. Farrow had adopted Moses Farrow, who was born on January 27, 1978. Mr. Allen preferred that Ms. Farrow’s children not be a part of their lives together. Until 1985, Mr. Allen had “virtually a single person’s relationship” with Ms. Farrow and viewed her children as an encumbrance. He had no involvement with them and no interest in them. Throughout their relationship, Mr. Allen has maintained his residence on the east side of Manhattan and Ms. Farrow has lived with her children on the west side of Manhattan.

In 1984, Ms. Farrow expressed a desire to have a child with Mr. Allen. He resisted, fearing that a young child would reduce the time that they had available for each other. Only after Ms. Farrow promised that the child would live with her and that Mr. Allen need not be involved with the child’s care or upbringing, did he agree.

After six months of unsuccessful attempts to become pregnant, and with Mr. Allen’s lukewarm support, Ms. Farrow decided to adopt a child. Mr. Allen chose not to participate in the adoption and Ms. Farrow was the sole adoptive parent. On July 11, 1985, the newborn Dylan joined the Farrow household.

Mr. Allen’s attitude toward Dylan changed a few months after the adoption. He began to spend some mornings and evenings at Ms. Farrow’s apartment in order to be with Dylan. He visited at Ms. Farrow’s country home in Connecticut and accompanied the Farrow-Previn family on extended vacations to Europe in 1987, 1988 and 1989. He remained aloof from Ms. Farrow’s other children except for Moses, to whom he was cordial.

In 1986, Ms. Farrow suggested the adoption of another child. Mr. Allen, buoyed by his developing affection for Dylan, was enthusiastic. Before another adoption could be arranged, Ms. Farrow became pregnant with Satchel.

During Ms. Farrow’s pregnancy, Mr. Allen did not touch her stomach, listen to the fetus, or try to feel it kick. Because Mr. Allen had shown no interest in her pregnancy and because Ms. Farrow believed him to be squeamish about the delivery process, her friend Casey Pascal acted as her Lamaze coach.

A few months into the pregnancy, Ms. Farrow began to withdraw from Mr. Allen. After Satchel’s birth, which occurred on December 19, 1987, she grew more distant from Mr. Allen. Ms. Farrow’s attention to Satchel also reduced the time she had available for Dylan. Mr. Allen began to spend more time with Dylan and to intensify his relationship with her.

By then, Ms. Farrow had become concerned with Mr. Allen’s behavior toward Dylan. During a trip to Paris, when Dylan was between two and three years old, Ms. Farrow told Mr. Allen that “[y]ou look at her [Dylan] in a sexual way. You fondled her. It’s not natural. You’re all over her. You don’t give her any breathing room. You look at her when she’s naked.”

Her apprehension was fueled by the intensity of the attention Mr. Allen lavished on Dylan, and by his spending play-time in bed with her, by his reading to her in his bed while dressed in his undershorts, and by his permitting her to suck on his thumb.

Ms. Farrow testified that Mr. Allen was overly attentive and demanding of Dylan’s time and attention. He was aggressively affectionate, providing her with little space of her own and with no respect for the integrity of her body. Ms. Farrow, Casey Pascal, Sophie Raven (Dylan’s French tutor), and Dr. Coates testified that Mr. Allen focused on Dylan to the exclusion of her siblings, even when Satchel and Moses were present.

In June 1990, the parties became concerned with Satchel’s behavior and took him to see Dr. Coates, with whom he then began treatment. At Dr. Coates’ request, both parents participated in Satchel’s treatment. In the fall of 1990, the parties asked Dr. Coates to evaluate Dylan to determine if she needed therapy. During the course of the evaluation, Ms. Farrow expressed her concern to Dr. Coates that Mr. Allen’s behavior with Dylan was not appropriate. Dr. Coates observed:

I understood why she was worried, because it [Mr. Allen’s relationship with Dylan] was intense, … I did not see it as sexual, but I saw it as inappropriately intense because it excluded everybody else, and it placed a demand on a child for a kind of acknowledgment that I felt should not be placed on a child …

She testified that she worked with Mr. Allen to help him to understand that his behavior with Dylan was inappropriate and that it had to be modified. Dr. Coates also recommended that Dylan enter therapy with Dr. Schultz, with whom Dylan began treatment in April 1991.

In 1991, Ms. Farrow expressed a desire to adopt another child. Mr. Allen, who had begun to believe that Ms. Farrow was growing more remote from him and that she might discontinue his access to Dylan, said that he would not take “a lousy attitude towards it” if, in return, Ms. Farrow would sponsor his adoption of Dylan and Moses. She said that she agreed after Mr. Allen assured her that “he would not take Dylan for sleep-overs . . . unless I was there. And that if, God forbid, anything should happen to our relationship, that he would never seek custody.” The adoptions were concluded in December 1991.

Until 1990, although he had had little contact with any of the Previn children, Mr. Allen had the least to do with Soon-Yi. “She was someone who didn’t like me. I had no interest in her, none whatsoever. She was a quiet person who did her work. I never spoke to her.” In 1990, Mr. Allen, who had four season tickets to the New York Knicks basketball games, was asked by Soon-Yi if she could go to a game. Mr. Allen agreed.

During the following weeks, when Mr. Allen visited Ms. Farrow’s home, he would say hello to Soon-Yi, “which is something I never did in the years prior, but no conversations with her or anything.”

Soon-Yi attended more basketball games with Mr. Allen. He testified that “gradually, after the basketball association, we became more friendly. She opened up to me more.” By 1991 they were discussing her interests in modeling, art, and psychology. She spoke of her hopes and other aspects of her life.

In September 1991, Soon-Yi entered Drew College in New Jersey. She was naive, socially inexperienced and vulnerable. Mr. Allen testified that she was lonely and unhappy at school, and that she began to speak daily with him by telephone. She spent most weekends at home with Ms. Farrow. There is no evidence that Soon-Yi told Ms. Farrow either that she was lonely or that she had been in daily communication with Mr. Allen.

On January 13, 1992, while in Mr. Allen’s apartment, Ms. Farrow discovered six nude photographs of Soon-Yi which had been left on the mantelpiece. She is posed reclining on a couch with her legs spread apart. Ms. Farrow telephoned Mr. Allen to confront him with her discovery of the photographs.

Ms. Farrow returned home, showed the photographs to Soon-Yi and said, “What have you done?” She left the room before Soon-Yi answered. During the following weekend, Ms. Farrow hugged Soon-Yi and said that she loved her and did not blame her. Shortly thereafter, Ms. Farrow asked Soon-Yi how long she had been seeing Mr. Allen. When Soon-Yi referred to her sexual relationship with Mr. Allen, Ms. Farrow hit her on the side of the face and on the shoulders. Ms. Farrow also told her older children what she had learned.

Ms. Farrow has commenced an action in the Surrogate’s Court to vacate Mr. Allen’s adoption of Dylan and Moses. In that proceeding, she contends that Mr. Allen began a secret affair with Soon-Yi prior to the date of the adoption. This issue has been reserved for consideration by the Surrogate and has not been addressed by me.

After receiving Ms. Farrow’s telephone call, Mr. Allen went to her apartment where, he said, he found her to be “ragingly angry.” She begged him to leave. She testified that:

[w]hen he finally left, he came back less than an hour later, and I was sitting at the table. By then, all of the children were there . . . and it was a rather silent meal. The little ones were chatting and he walked right in and he sat right down at the table as if nothing had happened and starts chatting with . . . the two little ones, said hi to everybody. And one by one the children [Lark, Daisy, Fletcher, Moses and Sascha] took their plates and left. And I’d, I didn’t know what to do. And then I went out.

Within the month, both parties retained counsel and attempted to negotiate a settlement of their differences. In an effort to pacify Ms. Farrow, Mr. Allen told her that he was no longer seeing Soon-Yi. This was untrue. A temporary arrangement enabled Mr. Allen to visit regularly with Dylan and Satchel but they were not permitted to visit at his residence. In addition, Ms. Farrow asked for his assurance that he would not seek custody of Moses, Dylan or Satchel.

On February 3, 1992, both parties signed documents in which it was agreed that Mr. Allen would waive custodial rights to Moses, Dylan and Satchel if Ms. Farrow predeceased him. On the same day, Mr. Allen signed a second document, which he did not reveal to Ms. Farrow, in which he disavowed the waiver, claiming that it was a product of duress and coercion and stating that “I have no intention of abiding by it and have been advised that it will not hold up legally and that at worst I can revoke it unilaterally at will.”

In February 1992, Ms. Farrow gave Mr. Allen a family picture Valentine with skewers through the hearts of the children and a knife through the heart of Ms. Farrow. She also defaced and destroyed several photographs of Mr. Allen and of Soon-Yi.

In July 1992, Ms. Farrow had a birthday party for Dylan at her Connecticut home. Mr. Allen came and monopolized Dylan’s time and attention. After Mr. Allen retired to the guest room for the night, Ms. Farrow affixed to his bathroom door, a note which called Mr. Allen a child molester. The reference was to his affair with Soon-Yi.

In the summer of 1992, Soon-Yi was employed as a camp counselor. During the third week of July, she telephoned Ms. Farrow to tell her that she had quit her job. She refused to tell Ms. Farrow where she was staying. A few days later, Ms. Farrow received a letter from the camp advising her that:

[it] is with sadness and regret that we had to ask Soon-Yi to leave camp midway through the first camp session … Throughout the entire orientation period and continuing during camp, Soon-Yi was constantly involved with telephone calls. Phone calls from a gentleman whose name is Mr. Simon seemed to be her primary focus and hits definitely detracted from her concentration on being a counselor.

Mr. Simon was Woody Allen.

On August 4, 1992, Mr. Allen travelled to Ms. Farrow’s Connecticut vacation home to spend time with his children. Earlier in the day, Casey Pascal had come for a visit with her three young children and their babysitter, Alison Stickland. Ms. Farrow and Ms. Pascal were shopping when Mr. Allen arrived. Those present were Ms. Pascal’s three children; Ms. Stickland; Kristie Groteke, a babysitter employed by Ms. Farrow; Sophie Berge, a French tutor for the children; Dylan; and Satchel.

Ms. Farrow had previously instructed Ms. Groteke that Mr. Allen was not to be left alone with Dylan. For a period of fifteen or twenty minutes during the afternoon, Ms. Groteke was unable to locate Mr. Allen or Dylan. After looking for them in the house, she assumed that they were outside with the others. But neither Ms. Berge nor Ms. Stickland was with Mr. Allen or Dylan. Ms. Groteke made no mention of this to Ms. Farrow on August 4.

During a different portion of the day, Ms. Stickland went to the television room in search of one of Ms. Pascal’s children. She observed Mr. Allen kneeling in front of Dylan with his head on her lap, facing her body. Dylan was sitting on the couch staring vacantly in the direction of a television set.

RELATED CONTENT. Moses Farrow – A Son Speaks Out

Casey’s nanny, Alison, would later claim that she walked into the TV room and saw Woody kneeling on the floor with his head in Dylan’s lap on the couch. Really? With all of us in there?

After Ms. Farrow returned home, Ms. Berge noticed that Dylan was not wearing anything under her sundress. She told asked Ms. Groteke to put underpants on Dylan.

Ms. Stickland testified that during the evening of August 4, she told Ms. Pascal, “I had seen something at Mia’s that day that was bothering me.” She revealed what she had seen in the television room. On August 5, Ms. Pascal telephoned Ms. Farrow to tell her what Ms. Stickland had observed. Ms. Farrow testified that after she hung up the telephone, she asked Dylan, who was sitting next to her, “whether it was true that daddy had his face in her lap yesterday.” Ms. Farrow testified:

Dylan said yes. And then she said that she didn’t like it one bit, no, he was breathing into her, into her legs, she said. And that he was holding her around the waist and I said, why didn’t you get up and she said she tried to but that he put his hands underneath her and touched her. And she showed me where . . . Her behind.

Because she was already uncomfortable with Mr. Allen’s inappropriate behavior toward Dylan and because she believed that her concerns were not being taken seriously enough by Dr. Schultz and Dr. Coates, Ms. Farrow videotaped Dylan’s statements. Over the next twenty-four hours, Dylan told Ms. Farrow that she had been with Mr. Allen in the attic and that he had touched her privates with his finger.

After Dylan’s first comments, Ms. Farrow telephoned her attorney for guidance. She was advised to bring Dylan to her pediatrician, which she did immediately. Dylan did not repeat the accusation of sexual abuse during this visit and Ms. Farrow was advised to return with Dylan on the following day. On the trip home, she explained to her mother that she did not like talking about her privates. On August 6, when Ms. Farrow went back to Dr. Kavirajan’s office, Dylan repeated that she had told her mother on August 5. A medical examination conducted on August 9 showed no physical evidence of sexual abuse.

Although Dr. Schultz was vacationing in Europe, Ms. Farrow telephoned her daily for advice. Ms. Farrow also notified Dr. Coates, who was still treating Satchel. She said to Dr. Coates, “it sounds very convincing to me, doesn’t it to you. It is so specific. Let’s hope it is her fantasy.” Dr. Coates immediately notified Mr. Allen of the child’s accusation and then contacted the New York City Child Welfare Administration. Seven days later, during a meeting of the lawyers at which settlement discussions were taking place, Mr. Allen began this action for custody.

Dr. Schultz returned from vacation on August 16. She was transported to Connecticut in Mr. Allen’s chauffeured limousine on August 17, 18 and 21 for therapy sessions with Dylan. Dylan, who had become increasingly resistant to Dr. Schultz, did not want to see her. During the third session, Dylan and Satchel put glue in Dr. Schultz’s hair, cut her dress and told her to go away.

On August 24 and 27, Ms. Farrow expressed to Dr. Schultz her anxiety about Dr. Schultz continuing to see Mr. Allen, who had already brought suit for custody of Dylan. She asked if Dr. Schultz would

. . . please not come for a while until all of this is settled down because . . . I couldn’t trust anybody. And she said she understood completely . . . And soon after that . . . I learned that Dr. Schultz had told [New York] child welfare that Dylan had not reported anything to her. And then a week later, either her lawyer or Dr. Schultz called [New York] child welfare and said she just remembered that Dylan had told her that Mr. Allen had put a finger in her vagina. When I heard that I certainly didn’t trust Dr. Schultz.

Dr. Schultz testified that on August 19, Paul Williams of the New York Child Welfare Administration asked about her experience with Dylan. She replied that on August 17, Dylan started to tell her what had happened with Mr. Allen but she needed more time to explore this with Dylan. On August 27, she spoke more fully to Mr. Williams about her August 17 session with Dylan and speculated about the significance of what Dylan reported. Mr. Williams testified that on August 19, Dr. Schultz told him that Dylan had not made any statements to her about sexual abuse.

Ms. Farrow did not immediately resume Dylan’s therapy because the Connecticut State Police had requested that she not be in therapy during the investigation. Also, it was not clear if the negotiated settlement that the parties were continuing to pursue would include Mr. Allen’s participation in the selection of Dylan’s new therapist.

Dr. Coates continued to treat Satchel through the fall of 1992. Ms. Farrow expressed to Dr. Coates her unease with the doctor seeing Mr. Allen in conjunction with Satchel’s therapy. On October 29, 1992, Ms. Farrow requested that Dr. Coates treat Satchel without the participation of Mr. Allen. Dr. Coates declined, explaining that she did not believe that she could treat Satchel effectively without the full participation of both parents. Satchel’s therapy with Dr. Coates was discontinued on November 28, 1992. At Ms. Farrow’s request, Dr. Coates recommended a therapist to continue Satchel’s therapy. Because of a conflict, the therapist recommended by Dr. Coates was unable to treat Satchel. He did, however, provide the name of another therapist with whom Satchel is currently in treatment.

On December 30, 1992, Dylan was interviewed by a representative of the Connecticut State Police. She told them—at a time Ms. Farrow calculates to be the fall of 1991—that while at Mr. Allen’s apartment, she saw him and Soon-Yi having sex. Her reporting was childlike but graphic. She also told the police that Mr. Allen had pushed her face into a plate of hot spaghetti and had threatened to do it again.

Ten days before Yale-New Haven concluded its investigation, Dylan told Ms. Farrow, for the first time, that in Connecticut, while she was climbing up the ladder to a bunk bed, Mr. Allen put his hands under her shorts and touched he Ms. Farrow testified that as Dylan said this, “she was illustrating graphically where in the genital area.”

Conclusions

A) Woody Allen

Mr. Allen has demonstrated no parenting skills that would qualify him as an adequate custodian for Moses, Dylan or Satchel. His financial contributions to the children’s support, his willingness to read to them, to tell them stories, to buy them presents, and to oversee their breakfasts, do not compensate for his absence as a meaningful source of guidance and caring in their lives. These contributions do not excuse his evident lack of familiarity with the most basic details of their day-to-day existences.

He did not bathe his children. He did not dress them, except from time to time, and then only to help them put on their socks and jackets. He knows little of Moses’ history, except that he has cerebral palsy; he does not know if he has a doctor. He does not know the name of Dylan and Satchel’s pediatrician. He does not know the names of Moses’ teachers or about his academic performance. He does not know the name of the children’s dentist. He does not know the names of his children’s friends. He does not know the names of any of their many pets. He does not know which children shared bedrooms. He attended parent-teacher conferences only when asked to do so by Ms. Farrow.

Mr. Allen has even less knowledge about his children’s siblings, with whom he seldom communicated. He apparently did not pay enough attention to his own children to learn from them about their brothers and sisters.

Mr. Allen characterized Ms. Farrow’s home as a foster care compound and drew distinctions between her biological and adopted children. When asked how he felt about sleeping with his children’s sister, he responded that “she [Soon-Yi] was an adopted child and Dylan was an adopted child.” He showed no understanding that the bonds developed between adoptive brothers and sisters are no less worthy of respect and protection than those between biological siblings.

Mr. Allen’s reliance on the affidavit which praises his parenting skills, submitted by Ms. Farrow in connection with his petition to adopt Moses and Dylan, is misplaced. Its ultimate probative value will be determined in the pending Surrogate’s Court proceeding. In the context of the facts and circumstances of this action, I accord it little weight.

None of the witnesses who testified on Mr. Allen’s behalf provided credible evidence that he is an appropriate custodial parent. Indeed, none would venture an opinion that he should be granted custody. When asked, even Mr. Allen could not provide an acceptable reason for a change in custody.

His counsel’s last question of him on direct examination was, “Can you tell the Court why you are seeking custody of your children?” Mr. Allen’s response was a rambling non sequitur which consumed eleven pages of transcript. He said that he did not want to take the children away from Ms. Farrow; that Ms. Farrow maintained a non-traditional household with biological children and adopted children from all over the world; that Soon-Yi was fifteen years older than Dylan and seventeen years older than Satchel; that Ms. Farrow was too angry with Mr. Allen to resolve the problem; and that with him, the children “will be responsibly educated” and “their day-to-day behavior will be done in consultation with their therapist.” The most relevant portions of the response — that he is a good father and that Ms. Farrow intentionally turned the children against him — I do not credit. Even if he were correct, under the circumstances of this case, it would be insufficient to warrant a change of custody.

Mr. Allen’s deficiencies as a custodial parent are magnified by his affair with Soon-Yi. As Ms. Farrow’s companion, he was a frequent visitor at Soon-Yi’s home. He accompanied the Farrow-Previns on extended family vacations and he is the father of Soon-Yi’s siblings, Moses, Dylan and Satchel. The fact that Mr. Allen ignored Soon- Yi for ten years cannot change the nature of the family constellation and does not create a distance sufficient to convert their affair into a benign relationship between two consenting adults.

Mr. Allen admits that he never considered the consequences of his behavior with Soon-Yi. Dr. Coates and Dr. Brodzinsky testified that Mr. Allen still fails to understand that what he did was wrong. Having isolated Soon-Yi from her family, he left her with no visible support system. He had no consideration for the consequences to her, to Ms. Farrow, to the Previn children for whom he cared little, or to his own children for whom he professes love.

Mr. Allen’s response to Dylan’s claim of sexual abuse was an attack upon Ms. Farrow, whose parenting ability and emotional stability he impugned without the support of any significant credible evidence. His trial strategy has been to separate his children from their brothers and sisters; to turn the children against their mother; to divide adopted children from biological children; to incite the family against their household help; and to set household employees against each other. His self-absorption, his lack of judgment and his commitment to the continuation of his divisive assault, thereby impeding the healing of the injuries that he has already caused, warrant a careful monitoring of his future contact with the children.

B) Mia Farrow

Few relationships and fewer families can easily bear the microscopic examination to which Ms. Farrow and her children have been subjected. It is evident that she loves children and has devoted a significant portion of her emotional and material wealth to their upbringing. When she is not working she attends to her children. Her weekends and summers are in Connecticut with her children. She does not take spent extended vacations unaccompanied by her children. She is sensitive to the needs of her children, respectful of their opinions, honest with them and quick to address their problems.

Mr. Allen elicited trial testimony that Ms. Farrow favored her biological children over her adopted children; that she manipulated Dylan’s sexual abuse complaint, in part through the use of leading questions and the videotape; that she discouraged Dylan and Satchel from maintaining a relationship with Mr. Allen; that she overreacted to Mr. Allen’s affair with Soon-Yi; and that she inappropriately exposed Dylan and Satchel to the turmoil created by the discovery of the affair.

The evidence at trial established that Ms. Farrow is a caring and loving mother who has provided a home for both her biological and her adopted children. There is no credible evidence that she unfairly distinguished among her children or that she favored some at the expense of others.

I do not view the Valentine’s Day card, the note affixed to the bathroom door in Connecticut, or the destruction of photographs as anything more than expressions of Ms. Farrow’s understandable anger and her ability to communicate her distress by word and symbol rather than by action.

There is no credible evidence to support Mr. Allen’s contention that Ms. Farrow coached Dylan or that Ms. Farrow acted upon a desire for revenge against him for seducing Soon-Yi.

RELATED CONTENT. Child Sexual Abuse Clinic Evaluation of Dylan Farrow

“… and third, that Dylan was coached or influenced by her mother, Ms. Farrow.”

Mr. Allen’s resort to the stereotypical “woman scorned” defense is an injudicious attempt to divert attention from his failure to act as a responsible parent and adult.

Ms. Farrow’s statement to Dr. Coates that she hoped that Dylan’s statements were a fantasy is inconsistent with the notion of brainwashing. In this regard, I also credit the testimony of Ms. Groteke, who was charged with supervising Mr. Allen’s August 4 visit with Dylan. She testified that she did not tell Ms. Farrow, until after Dylan’s statement of August 5, that Dylan and Mr. Allen were unaccounted for during fifteen or twenty minutes on August 4. It is highly unlikely that Ms. Farrow would have encouraged Dylan to accuse her father of having sexually molested her during a period in which Ms. Farrow believed they were in the presence of a babysitter. Moreover, I do not believe that Ms. Farrow would have exposed her daughter and her other children to the consequences of the Connecticut investigation and this litigation if she did not believe the possible truth of Dylan’s accusation.

In a society ‘where children are too often betrayed by adults who ignore or disbelieve their complaints of abuse, Ms. Farrow’s determination to protect Dylan is commendable. Her decision to videotape Dylan’s statements, although inadvertently compromising the sexual abuse investigation, was understandable.

Ms. Farrow is not faultless as a parent. It seems probable, although there is no credible testimony to this effect, that prior to the affair with Mr. Allen, Soon-Yi was experiencing problems for which Ms. Farrow was unable to provide adequate support. There is also evidence that there were problems with her relationships with Dylan and Satchel. We do not, however, demand perfection as a qualification for parenting. Ironically, Ms. Farrow’s principal shortcoming with respect to responsible parenting appears to have been her continued relationship with Mr. Allen.

Ms. Farrow reacted to Mr. Allen’s behavior with her children with a balance of appropriate caution, and flexibility. She brought her early concern with Mr. Allen s relationship with Dylan to Dr. Coates and was comforted by the doctor’s assurance that Mr. Allen was working to correct his behavior with the child. Even after January 13, 1992, Ms. Farrow continued to provide Mr. Allen with access to her home and to their children, as long as the visits were supervised by a responsible adult. She did her best, although with limited success, to shield her younger children from the turmoil generated by Mr. Allen’s affair with Soon-Yi.

Ms. Farrow’s refusal to permit Mr. Allen to visit with Dylan after August 4, 1992 was prudent. Her willingness to allow Satchel to have regular supervised visitation with Mr. Allen reflects her understanding of the propriety of balancing Satchel’s need for contact with his father against the danger of Mr. Allen’s lack of parental judgment. Ms. Farrow also recognizes that Mr. Allen and not Soon-Yi is the person responsible for their affair and its impact upon her family. She has communicated to Soon-Yi that she continues to be a welcome member of the Farrow-Previn home.

C) Dylan Farrow

Mr. Allen’s relationship with Dylan remains unresolved. The evidence suggests that it is unlikely that he could be successfully prosecuted for sexual abuse. I am less certain, however, than is the Yale-New Haven team, that the evidence proves conclusively that there was no sexual abuse.

Both Dr. Coates and Dr. Schultz expressed their opinions that Mr. Allen did not sexually abuse Dylan. Neither Dr. Coates nor Dr. Schultz has expertise in the field of child sexual abuse. I believe that the opinions of Dr. Coates and Dr. Schultz may have been colored by their loyalty to Mr. Allen. I also believe that therapists would have a natural reluctance to accept the possibility that an act of sexual abuse occurred on their watch. I have considered their opinions, but do not find their testimony to be persuasive with respect to sexual abuse or visitation.

I have also considered the report of the Yale-New Haven team and the deposition testimony of Dr. John M. Leventhal. The Yale-New Haven investigation was conducted over a six-month period by Dr. Leventhal, a pediatrician; Dr. Julia Hamilton, who has a Ph.D. in social work; and Ms. Jennifer Sawyer, who has a master’s degree in social work. Responsibility for different aspects of the investigation was divided among the team. The notes of the team members were destroyed prior to the issuance of the report, which, presumably, is an amalgamation of their independent impressions and observations. The unavailability of the notes, together with their unwillingness to testify at this trial except through the deposition of Dr. Leventhal, compromised my ability to scrutinize their findings and resulted in a report which was sanitized and, therefore, less credible.

Dr. Stephen Herman, a clinical psychiatrist who has extensive familiarity with child abuse cases, was called as a witness by Ms. Farrow to comment on the Yale-New Haven report. I share his reservations about the reliability of the report.

Dr. Herman faulted the Yale-New Haven team (1) for making visitation recommendations without seeing the parent interact with the child; (2) for failing to support adequately their conclusion that Dylan has a thought disorder; (3) for drawing any conclusions about Satchel, whom they never saw; (4) for finding that there was no abuse when the supporting data was inconclusive; and (5) for recommending that Ms. Farrow enter into therapy. In addition, I do not think that it was appropriate for Yale-New Haven, without notice to the parties or their counsel, to exceed its mandate and make observations and recommendations which might have an impact on existing litigation in another jurisdiction.

Unlike Yale-New Haven, I am not persuaded that the videotape of Dylan is the product of leading questions or of the child’s fantasy.

Richard Marcus, a retired New York City police officer, called by Mr. Allen, testified that he worked with the police sex crimes unit for six years. He claimed to have an intuitive ability to know if a person is truthful or not. He concluded, “based on my experience,” that Dylan lacked credibility.

I did not find his testimony to be insightful. I agree with Dr. Herman and Dr. Brodzinsky that we will probably never know what occurred on August 4, 1992. The credible testimony of Ms. Farrow, Dr. Coates, Dr. Leventhal and Mr. Allen does, however, prove that Mr. Allen’s behavior toward Dylan was grossly inappropriate and that measures must be taken to protect her.

D) Satchel Farrow

Mr. Allen had a strained and difficult relationship with Satchel during the earliest years of the child’s life. Dr. Coates testified, “Satchel would push him away, would not acknowledge him. . . . If he would try to help Satchel getting out of bed or going into bed, he would kick him, at times had scratched his face. They were in trouble.” Dr. Coates also testified that as an infant, Satchel would cry when held by Mr. Allen and stop when given to Ms. Farrow. Mr. Allen attributes this to Ms. Farrow’s conscious effort to keep him apart from the child.

Although Ms. Farrow consumed much of Satchel’s attention, and did not foster a relationship with his father, there is no credible evidence to suggest that she desired to exclude Mr. Allen. Mr. Allen’s attention to Dylan left him with less time and patience for Satchel. Dr. Coates attempted to teach Mr. Allen how to interact with Satchel. She encouraged him to be more understanding of his son when Satchel ignored him or acted bored with his gifts. Apparently, success in this area was limited.

In 1991, in the presence of Ms. Farrow and Dylan, Mr. Allen stood next to Satchel’s bed, as he did every morning. Satchel screamed at him to go away. When Mr. Allen refused to leave, Satchel kicked him. Mr. Allen grabbed Satchel’s leg, started to twist it. Ms. Farrow testified that Mr. Allen said “I’m going to break your fucking leg.” Ms. Farrow intervened and separated Mr. Allen from Satchel. Dylan told the Connecticut State Police about this incident.

That Mr. Allen now wants to spend more time with Satchel is commendable. If sincere, he should be encouraged to do so, but only under conditions that promote Satchel’s well being.

E) Moses Farrow

Mr. Allen’s interactions with Moses appear to have been superficial and more a response to Moses’ desire for a father—in a family where Mr. Previn was the father of the other six children—than an authentic effort to develop a relationship with the child. When Moses asked, in 1984, if Mr. Allen would be his father, he said “sure” but for years did nothing to make that a reality.

They spent time playing baseball, chess and fishing. Mr. Allen encouraged Moses to play the clarinet. There is no evidence, however, that Mr. Allen used any of their shared areas of interest as a foundation upon which to develop a deeper relationship with his son. What little he offered—a baseball catch, some games of chess, adoption papers—was enough to encourage Moses to dream of more, but insufficient to justify a claim for custody.

After learning of his father’s affair with his sister, Moses handed to Mr. Allen a letter that he had written. It states:

… you can’t force me to live with you. …. You have done a horrible, unforgivable, needy, ugly, stupid thing … about seeing me for lunch, you can just forget about that … we didn’t do anything wrong … All you did is spoil the little ones, Dylan and Satchel. … Everyone knows not to have an affair with your son’s sister … I consider you my father anymore. It was a great feeling having a father but you smashed that feeling and dream with a single act. I HOPE YOU ARE PROUD TO CRUSH YOUR SON’S DREAM.

Mr. Allen responded to this letter by attempting to wrest custody of Moses from his mother. His rationale is that the letter was generated by Ms. Farrow. Moses told Dr. Brodzinsky that he wrote the letter and that he did not intend for it to be seen by his mother.

Custody

Section 240(1) of the Domestic Relations Law states that in a custody dispute, the court must “give such direction … as… justice requires, having regard to the circumstances of the case and of the respective parties and to the best interests of the child.”

The case law of this state has made clear that the governing consideration is the best interests of the child. Eschbach v. Eschbach, 56 NY2d 167 (1982); Friederwitzer v. Friederwitzer, 55 NY2d 89 (1982).

The initial custodial arrangement is critically important. “Priority, not as an absolute but as a weighty factor, should, in the absence of extraordinary circumstances, be accorded to the first custody awarded in litigation or by voluntary agreement.” Nehra v. Uhlar, 43 NY2d 242, 251 (1977).

“[W]hen children have been living with one parent for a long period of time and the parties have previously agreed that custody shall remain in that parent, their agreement should prevail and custody should be continued unless it is demonstrated that the custodial parent is unfit or perhaps less fit (citations omitted).” Martin v. Martin, 74 AD2d 419, 426 (4th Dept 1980).

After considering Ms. Farrow’s position as the sole care-taker of the children, the satisfactory fashion in which she has fulfilled that function, the parties’ pre-litigation acceptance that she continue in that capacity, and Mr. Allen’s serious parental inadequacies, it is clear that the best interests of the children will be served by their continued custody with Ms. Farrow.

Visitation, like custody, is governed by a consideration of the best interests of the child. Miriam R. v. Arthur D.R., 85 AD2d 624 (2d Dept 1981). Absent proof to the contrary, the law presumes that visitation is in the child’s best interests. Wise v. Del Toro, 122 AD2d 714 (1st Dept 1986). The denial of visitation to a noncustodial parent must be accompanied by compelling reasons and substantial evidence that visitation is detrimental to the child’s welfare. Matter of Farrugia Children, 106 AD2d 293 (1st Dept 1984); Gowan v. Menqa, 178 AD2d 1021 (4th Dept 1991). If the noncustodial parent is a fit person and there are no extraordinary circumstances, there should be reasonable visitation. Hotze v. Hotze, 57 AD2d 85 (4th Dept 1977), appeal denied 42 N12d 805.

The overriding consideration is the child’s welfare rather than any supposed right of the parent. Weiss v. Weiss, 52 NY2d 170, 174-5 (1981); Hotze v. Hotze, supra at 87. Visitation should be denied where it may be inimical to the child’s welfare by producing serious emotional strain or disturbance. Hotze v. Hotze, supra at 88; see also Miriam R. v. Arthur D.R., supra; cf., State ex rel. H.K. v. M.S., 187 AD2d 50 (1st Dept 1993).

This trial included the observations and opinions of more mental health workers than is common to most custody litigation. The parties apparently agreed with Dr. Herman’s conclusion that another battery of forensic psychological evaluations would not have been in the children’s best interest and would have added little to the available information. Accordingly, none was ordered.

The common theme of the testimony by the mental health witnesses is that Mr. Allen has inflicted serious damage on the children and that healing is necessary. Because, as Dr. Brodzinsky and Dr. Herman observed, this family is in an uncharted therapeutic area, where the course is uncertain and the benefits unknown, the visitation structure that will best promote the healing process and safeguard the children is elusive. What is clear is that Mr. Allen’s lack of judgment, insight and impulse control make normal noncustodial visitation with Dylan and Satchel too risky to the children’s well-being to be permitted at this time.

A) Dylan

Mr. Allen’s request for immediate visitation with Dylan is denied. It is unclear whether Mr. Allen will ever develop the insight and judgment necessary for him to relate to Dylan appropriately. According to Dr. Brodzinsky, even if Dylan was not sexually abused, she feels victimized by her father’s relationship with her sister. Dylan has recently begun treatment with a new therapist. Now that this trial is concluded, she is entitled to the time and space necessary to create a protective environment that will promote the therapeutic process. A significant goal of that therapy is to encourage her to fulfill her individual potential, including the resilience to deal with Mr. Allen in a manner which is not injurious to her.

The therapist witnesses agree that Mr. Allen may be able to serve a positive role in Dylan’s therapy. Dr. Brodzinsky emphasized that because Dylan is quite fragile and more negatively affected by stress than the average child, she should visit with Mr. Allen only within a therapeutic context. This function, he said, should be undertaken by someone other than Dylan’s treating therapist. Unless it interferes with Dylan’s individual treatment or is inconsistent with her welfare, this process is to be initiated within six months. A further review of visitation will be considered only after we are able to evaluate the progress of Dylan’s therapy.

B) Satchel

Mr. Allen’s request for extended and unsupervised visitation with Satchel is denied. He has been visiting regularly with Satchel, under supervised conditions, with the consent of Ms. Farrow. I do not believe that Ms. Farrow has discouraged Satchel’s visitation with Mr. Allen or that she has, except for restricting visitation, interfered with Satchel’s relationship with his father.

Although, absent exceptional circumstances, a non-custodial parent should not be denied meaningful access to a child, “supervised visitation is not a deprivation to meaningful access.” Lightbourne v. Lightbourne, 179 AD2d 562 (1st Dept 1992).

I do not condition visitation out of concern for Satchel’s physical safety. My caution is the product of Mr. Allen’s demonstrated inability to understand the impact that his words and deeds have upon the emotional well being of his children.

I believe that Mr. Allen will use Satchel in an attempt to gain information about Dylan and to insinuate himself into her good graces. I believe that Mr. Allen will, if unsupervised, attempt to turn Satchel against the other members of his family. I believe Mr. Allen to be desirous of introducing Soon-Yi into the visitation arrangement without concern for the effect on Satchel, Soon-Yi or the other members of the Farrow family. In short, I believe Mr. Allen to be so self-absorbed, un-trustworthy and insensitive, that he should not be permitted to see Satchel without appropriate professional supervision until Mr. Allen demonstrates that supervision is no longer necessary. The supervisor should be someone who is acceptable to both parents, who will be familiarized with the history of this family and who is willing to remain in that capacity for a reasonable period of time. Visitation shall be of two hours’ duration, three times weekly, and modifiable by agreement of the parties.

C) Moses

Under the circumstances of this case, giving respect and credence to Ms. Farrow’s appreciation of her son’s sensitivity and intelligence, as confirmed by Dr. Brodzinsky, I will not require this fifteen-year-old child to visit with his father if he does not wish to do so.

If Moses can be helped by seeing Mr. Allen under conditions in which Moses will not be overwhelmed, then I believe that Ms. Farrow should and will promote such interaction. I hope that Moses will come to understand that the fear of demons often cannot be dispelled without first confronting them.

Counsel Fees

Ms. Farrow’s application for counsel fees is granted. Mr. Allen compounded the pain that he inflicted upon the Farrow family by bringing this frivolous petition for custody of Dylan, Satchel and Moses.

Domestic Relations Law §237(b) provides that upon an application for custody or visitation, the court may direct a parent to pay the counsel fees of the other parent “as, in the court’s discretion, justice requires, having regard to the circumstances of the case and of the respective parties.”

Ms. Farrow admits to a substantial net worth, although she is not nearly as wealthy as Mr. Allen. Clearly, she is able to absorb the cost of this litigation, although it has been extraordinarily expensive. However, “[i]ndigency is not a prerequisite to an award of counsel fees (citation omitted). Rather, in exercising its discretionary power to award counsel fees, a court should review the financial circumstances of both parties together with all the other circumstances of the case, which may include the relative merit of the parties’ positions.” DeCabre v. Cabrera-Rosete, 70 NY2d R79 881 (1987). Because Mr. Allen’s position had no merit, he will bear the entire financial, burden of this litigation. If the parties are unable to agree on Ms. Farrows reasonable counsel fees, a hearing will be conducted for that purpose.

Settle judgment.

DATED: June 7, 1993.

J.S.C.